Receba nossas newsletters

É de graça. Só tem coisa fina, você vai curtir!

Leia esta reportagem em português

LET HE WHO HAS NOT LEFT or been removed from a WhatsApp group at the time of the 2018 elections — because of some visceral disagreement with certain members of other political spectrums — cast the first emoji.

The presidential race split families, friendships, and also virtual groups, and has radically changed the way Brazilians use WhatsApp, promoting a more critical look at the information received on this network, and motivating the creation of clearer rules of conduct to regulate behavior within groups.

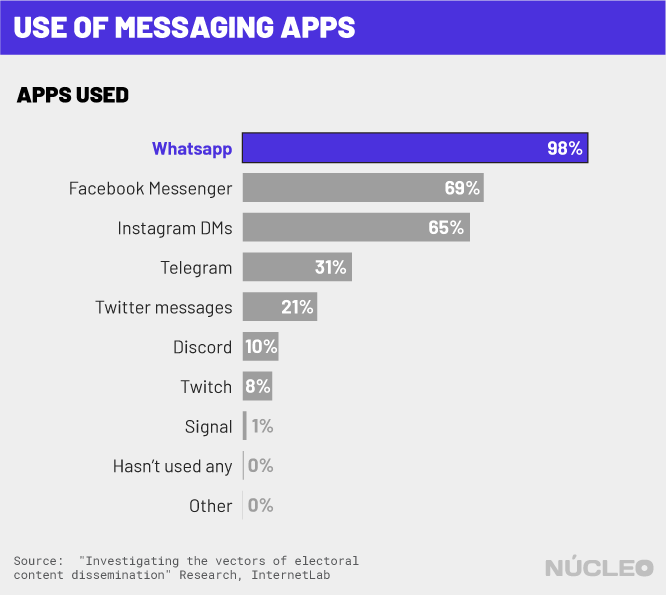

The conclusion is based on an extensive survey on WhatsApp use conducted by InternetLab in partnership with Rede Conhecimento Social (Social Knowledge Network), which Núcleo uncovers exclusively. The study has more than 3,100 respondents and is representative of the population age 16+ that uses the internet.

Two main points about behavioral changes stand out in the survey:

- 71% of respondents said they changed their behavior on the app after the 2018 election, even to the point of restraining themselves in their replies in groups;

- Half said they had noticed changes in the rules of group coexistence, about what could and could not be shared in them.

With under a year to go until the 2022 elections, which promise to be as or more polarized than the previous ones, these small but important changes are constantly put to the test — especially because there is nowhere to turn, considering that WhatsApp, which belongs to Facebook, dominates the messaging market in the country and is present in almost all Brazilian cell phones.

Also relevant is the role of groups, which represent a huge part of the interaction between people on the app: 95% of the app's users are in at least one.

"I DON'T KNOW HOW MANY GROUPS I'M IN AND I THINK IT SHOULD BE A FEATURE OF WHATSAPP TO SHOW HOW MANY. THERE ARE GROUPS THAT I MUTE AND NEVER READ. NOT TO MENTION THOSE THAT WE ARE SUPPOSED TO DELETE LATER AND NEVER DO. I'M CERTAINLY IN MORE THAN 20." - Respondent from a capital in the Southern Region

About the research

InternetLab and Rede Conhecimento Social collected data from an online panel and recorded 3,113 interviews between Dec. 7 and 16, 2020. The population considered consisted of people aged 16 and over with access to internet and WhatsApp use.

The margin of error is 3 percentage points, with a confidence interval of 95%. The sample is proportional to the population studied, according to the authors.

There was also previous qualitative research with seven focus groups of seven or eight people, from various regions.

See the full survey results.

Affection and lies

Much of what has generated these changes can be attributed to two main factors:

1. affection;

2. fear of misinformation.

The first element is due to more personal reasons, since political polarization has generated unease in close-knit groups of people and friction in family relationships, friendships, and sometimes even professional relations, as explained to Núcleo by Heloisa Massaro, research coordinator in the Information and Politics division at InternetLab, and Fernanda Império, consultant at Rede Conhecimento Social.

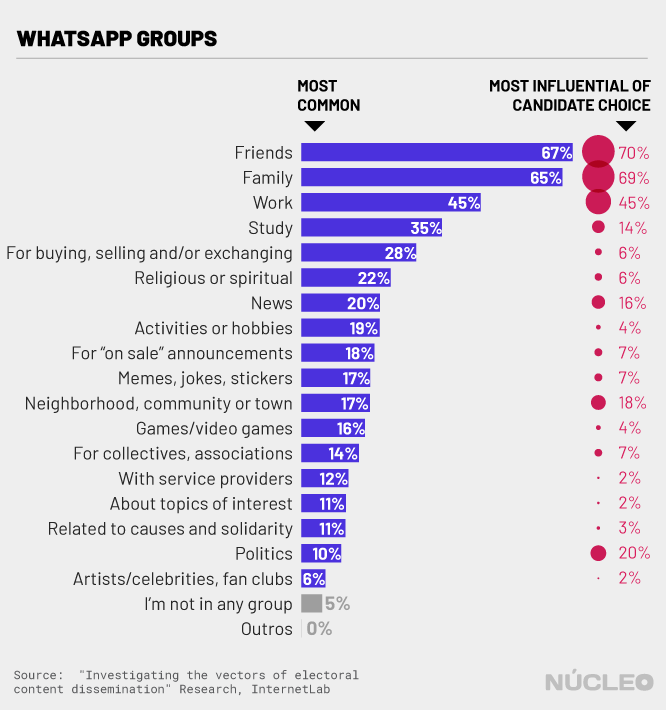

Family and friend groups, followed by work groups, are the most common on WhatsApp for the Brazilians heard in the survey. Not surprisingly, these are also the groups where people most talk about political news and were pointed out as the groups that have the greatest power to influence the choice of a political candidate.

"IN 2018 I ALSO LEFT THE DANCE GROUP, WHICH WAS A GROUP THAT I DANCED IN FOR 15 YEARS HERE IN MY CITY, AND IT WAS MORE OF THE SAME: POLITICAL STUFF. THE GROUP WAS QUITE SPREAD OUT, PEOPLE FROM ALL CORNERS OF BRAZIL AND WITH THAT CAME A NUMBER OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL MESSAGES. SO, IN ORDER NOT TO GET INTO FIGHTS, I PREFER TO LEAVE. I LEAVE BECAUSE IT’S BETTER TO KEEP THE FRIENDSHIP. – Respondent from the Rural Midwest

A second factor that may explain the post-2018 behavioral change and that showed up less spontaneously in the survey is linked to a greater fear of unintentionally spreading misinformation.

Users have created their own ethics regarding "fake news," a behavior that has been observed among self-declared left-wing and right-wing people.

IT IS IMPORTANT TO POINT OUT, HOWEVER, THAT THE UNDERSTANDING OF WHAT IT MEANS TO CHECK FOR FAKE NEWS VARIES BETWEEN GROUPS — BUT THE CONCERN, IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER, IS THERE.

"That personal ethic is going to depend on how the person reads the world or the information ecosystem they are in," said InternetLab's Heloisa Massaro.

"So what it means to check a source is different from person to person. The emergence of an ethic in itself is not necessarily something positive or negative. What that ethic is depends widely on where the person is situated," she assessed.

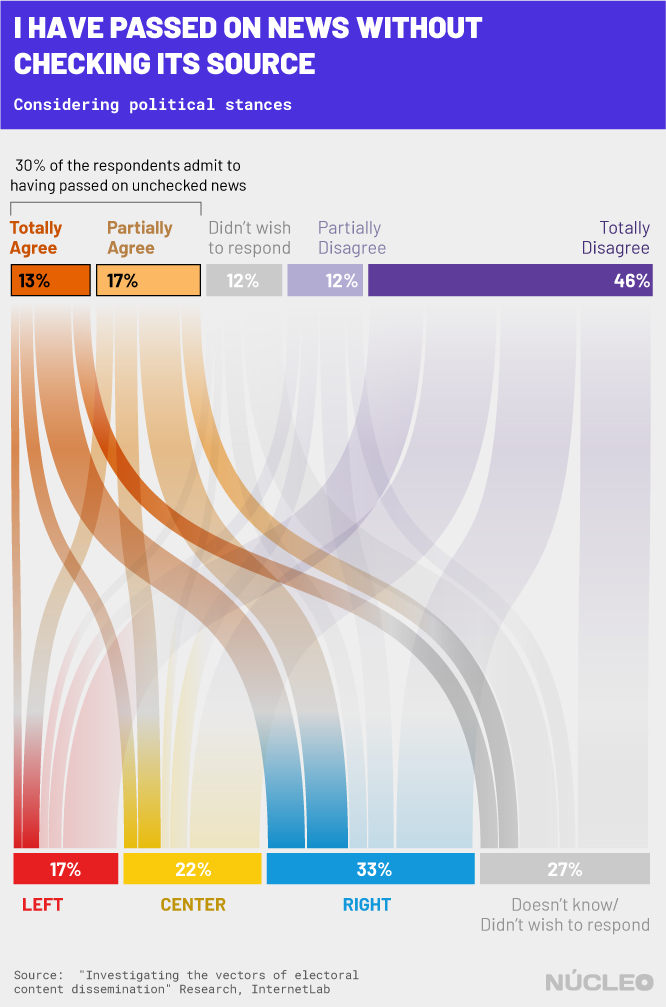

Even so, 30% of the respondents admitted, at least partially, to having passed on news without checking the source of the information. Right-wing respondents were more willing to admit to this — 40% admitted to having done so, while only 25% on the left did so.

To prove that polarization on WhatsApp is not going away anytime soon, 1 in 3 respondents said they share potentially offensive content when they believe in an idea, along the lines of the so-called "confirmation bias" that is so present in the misinformation landscape.

IF IT APPLIES OFFLINE, IT APPLIES ONLINE

WhatsApp is not a homogeneous network — and neither are its groups. Besides the technical limitations imposed by the tool, such as forwarding limits and limits to viral messages, there is no rulebook that applies to all groups.

The research also showed that even in groups of 'similar types' , such as buying and selling groups, the specific rules can diverge considerably.

For Massaro, the norms are established on a very case-by-case basis, since the structure of a group is directly intertwined with people's relationships. This means that many rules and behavioral decisions are transferred from the offline to the online realm, emulating face-to-face interactions.

"SO, IT MAKES NO DIFFERENCE WHETHER I SAY IT IN THE FAMILY GROUP, IN WHATSAPP, OR AT A SUNDAY LUNCH. IT'S THE SAME FILTER. SO, THERE ARE GROUPS WHERE I FEEL COMFORTABLE, AND THERE ARE GROUPS WHERE I DON'T FEEL COMFORTABLE. THERE ARE PEOPLE I'VE NEVER SEEN IN MY LIFE, SO HOW AM I SUPPOSED TO INTERACT. WHEN I START TO INTERACT IT'S LIKE I'M JOINING A GROUP WHERE I DON'T KNOW ANYONE. IT'S THE SAME!" – Respondent from a capital in the Southern region

In some groups, where administrators are more incisive and active, such as those of a commercial or religious nature, the rules are at the core of the message exchange, and taking part in them means to consent to the proposed terms.

In more informal groups, such as Education groups, according to the researchers, the rules are formulated as the group develops, in a sort of consensus.

"IT'S A LIBRARY, SO EVERY TIME SOMEONE SAYS GOOD MORNING OR SOMETHING LIKE THAT, THE GROUP MANAGER SAYS HEY, THIS IS A LIBRARY! I'M IN A LIBRARY, I HAVE TO BE QUIET BECAUSE I'M GOING TO DISTURB A COLLEAGUE WHO IS READING. SO, IT IS THE GROUP THAT HAS THE MOST SEVERE RULE. ONE OF THE RULES IS EXPULSION FROM THE GROUP." – Respondent from a capital in the Northern region

SUBGROUPS

Another common behavior among Brazilians heard in the survey was the division of larger groups into smaller groups, among people who share the same political stances or who would be willing to talk about politics.

At least 42% of those consulted by the survey said they had seen the splitting of friend groups into smaller groups.

"The person in a way still remains in the large group, but seeks companionship in a smaller group to comment on the large group itself," said Fernanda Império of Rede Conhecimento Social.

The subdivision of groups was also observed in similar ways among people on the left and the right, according to the researchers.

This observation, by the way, permeated the research, Massaro explained. At several moments during the focus groups — one of the methods used in this research — it was not possible to distinguish a person's political position by the behavior they narrated.

2018 AGAIN?

One of the consequences of this behavioral change on WhatsApp is a greater skepticism or distrust by users regarding political communication strategies on the messaging app.

More than half of the respondents said they were passively reached by political groups in the 2020 municipal elections, either by receiving a link to a group or being added to a group by someone they knew. Only 18% report having asked to join these collective discussion spaces.

If the portion of people who receive invitations or are included in groups is high, the portion of those who stay is smaller, explained Fernanda Império. According to her, with the behavioral changes, people now delete and leave groups in which they are added without consent, which used to happen less before.

For the researchers, the behavioral change in this direction reinforces how communication tactics and political propaganda used in past elections will no longer be as effective from now on.

In Oct. 2018, a Folha de S. Paulo investigative report revealed that businessmen financed contracts of up to R$12 million with companies that disseminated bulk messages contrary to Brazil’s Workers’ Party (PT) on WhatsApp.

"This contrast in data reveals the tension between what campaigns' strategy tactics are when they wish to use a tool and how that has to do with the way people use and perceive that app," explained InternetLab's Massaro.

"There's no point in getting everyone's number and sending everyone a link if it's not connected to the way people relate to the app. If it doesn't make sense to them, it may not be effective at all," the researcher added.In any case, WhatsApp is still a precious tool for the electoral apparatus. According to the survey, information received through the app was relevant enough for 36% of Brazilians to decide on their votes in the 2020 municipal elections.

HOW WE DID IT

InternetLab and the Rede Conhecimento Social first provided Núcleo the results and data from the survey. We analyzed this information and interviewed the research coordinators behind it.

The organizations collected data from an online panel and recorded 3,113 interviews between Dec. 7 and 16, 2020. The population considered consisted of people aged 16 and over with access to the internet and WhatsApp use. The margin of error is 3 percentage points, with a confidence interval of 95%. The sample is proportional to the population studied, according to the authors.There was also a previous qualitative survey with seven focus groups of seven or eight people, from various regions.

The research was financially supported by WhatsApp itself, but was conducted independently by the organizations.

Authors' note:

This research was conducted independently by InternetLab and Rede Conhecimento Social, with the support of a financial donation from the company. Following InternetLab’s funding policy and,according to the contractual provision, WhatsApp had no interference in the research design, data collection and analysis, nor the organization of the results.

The survey and sample data can be accessed at this link.